Suppose Google was Compromised

01 January 2022

Threat modeling is the information security practice of anticipating and mitigating negative outcomes in physical and digital systems, most often unauthorized access, theft, and vandalism. In my discipline, a solid understanding of threat modeling can not only help your teams to build software which is resistant to attackers, but it can help you personally by sharpening your ability to measure and avoid unnecessary risk in everyday life.

I thought it would be fun to practice this skill on a novel scenario. Even better if its something apparently nobody has ever solved or published resources for on the internet, but that could really help a vulnerable population if such a resource existed.

The Scenario:

So say, hypothetically, that you were a survivor of domestic abuse, who has accepted a job in a new city. Let’s say that your abuser, who also lives in this city, has a history of stalking and physical violence. Hell, let’s make it really interesting, let’s assume that they are a programmer working for a multi-billion dollar tech company with an extensive portfolio of digital surveillance tools, are intellectually and technologically quite gifted, and sufficiently motivated to cause you harm if the right opportunity presented itself. For example:

What if your abuser works at Google?

That sounds like a really difficult situation doesn’t it? You might even be tempted to self-select out of this career opportunity entirely, out of fear. But maybe you’ve done that before, several times, and are really, really fucking tired of it. Maybe you didn’t ask for any of this. And maybe you want to take some control back in your life, have the right to live where you please, and deserve equitable access to opportunities that would honestly be really good for you. So let’s assume that you’ve decided to take the job, move across the country, and invest in protecting yourself by whatever means necessary.

I think this scenario creates a lot of really interesting questions. There’s so much discourse today about whether companies can be responsible stewards of your data (they can’t) or should be trusted with such immense power (they shouldn’t). But forget corporations; is it even possible, in this connected age, to keep yourself safe from an individual who has access to exponentially more resources than you? What would that look like? And is it possible to teach survivors, who may be starting on their back foot already, how to do it?

We’ll learn about three basic tools for threat modeling today: the persona non grata, the STRIDE risk modeling method, and attack trees.

Know Thy Enemy

First, we should probably paint a clear picture of our adversary. To do that, lets create a Persona non Grata, or PnG. These are kind of like user personas in most Agile methodologies, except they’re specific to individuals who introduce risk. Software development companies and government agencies alike use this and similar formats to help narrow down the most likely attack vectors in complex systems.

A PnG should have some or, ideally, all of these things:

Name: Since oftentimes you’ll have multiple attackers, it’s important to be able to specify which one you have in mind when brainstorming. Our attacker is totally fictional, though, and any resemblance to real life events or people is absolutely a coincidence. How about Person McPersonface? Classic.

Context: It can be really helpful to understand why an attacker has chosen to compromise your system, in order to think like them and close off common weak points they’re likely to exploit. Let’s add some things that we know about McPersonface based on our history with him that we don’t have, because he isn’t real.

Goals: What does McPersonface actually want, at the end of the day?

Skills & Resources: What does McPersonface have at his disposal, that makes him dangerous?

Our completed PnG might look something like this:

Person McPersonface, Software Engineer

Vengeful, with a Flaccid, Impotent Penis

Context:

McPersonface is an ex-partner who is physically and emotionally violent. As a software developer, they have substantial skill in writing programs for niche or spite-based purposes, and are comfortable with mechanical engineering when necessary. Remarkably possessive and controlling: has previously leveraged IoT devices and data streams to monitor and stalk partners without consent. Used to have access to many of your physical devices and passwords, as well as your house key. Has powerful industry contacts and may have physical access to Google hardware and databases. Openly proud of their ability to “manipulate optics” of any situation. Once maintained a list of ways to emotionally destroy each person they’ve ever been close to, which is not normal behavior for any human being. Has expressed that they specifically consider you a threat when in shared social circles. Has demonstrated disregard for ethics and the comfort of others in the pursuit of self-gratification.

Goals:

- Make unwanted contact, either to hoover you back into an abusive orbit, or silence you.

- If that fails: create a hostile environment so that you leave.

- If that fails: socially isolate you from others to minimize threat to self.

- If that fails, at least collect data on you so that you can be monitored.

Skills & Resources:

- Programming

- Social engineering, is a persuasive speaker

- FAANG money

- Access to Google services

- Picks locks

- Proficiency building or modifying physical hardware.

- Is bigger than you

Attack trees

This exercise was useful to paint a picture of our adversary, but it could still use some work. I don’t mean my beautiful crayon art; that’s perfect. I mean that the attacker’s goals are too nonspecific. We understand their motivation a bit better now, but “making unwanted contact” could mean a lot of different things and be accomplished in many ways. So, as a next step, let’s enumerate the possible negative outcomes. What are we afraid of, specifically? The attacker could:

- Gain physical entry to our new home for purposes of violence or intimidation.

- Follow us somewhere else.

- Access hardware or digital accounts and use them in ways that are unpleasant.

- Gather private information about our lives to use later.

- Profile, influence, or endanger loved ones.

We don’t know that any of these are our adversary’s goals today, but they are certainly ways in which that goal could be achieved and are therefore worth considering and protecting against. You may also notice that some of them beget additional, negative outcomes which we haven’t thought of yet. They got us started, but maybe bulleted lists aren’t the right tool for this job.

In order to help us visualize the relationships between potential negative outcomes, and the way those outcomes could be achieved, we can instead create something like an attack tree. An attack tree is a visual hierarchy of each of the attacker’s potential goals, and the individual options and requirements for the attacker to achieve each. To create an attack tree, you list each of the top-level negative outcomes that could occur, and then connecting nodes for what would be required for it to happen.

This is incomplete, but you get the idea!

For best results, you’ll want to share this with someone and get feedback. Threat modeling is best as a collaborative activity, since your partners are likely to think of methods of attack that you would not. Also it’s just kinda fun?

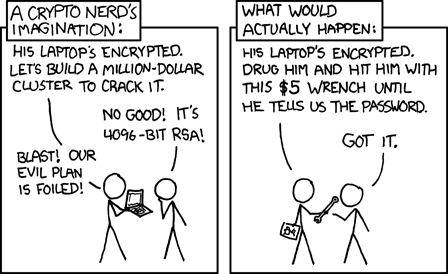

In a corporate setting, you might also assign additional values to each node such as its probability, or how much money each option would cost an attacker, to help you focus on the most important weaknesses first. It also helps you avoid having your elaborate plans foiled by a five dollar wrench.

XKCD #538

Now we’re starting to get a picture of our attack surface; an exhaustive list of all of the vectors by which the PnG could cause harm. Sometimes these vulnerabilities are obvious, but others are more creative and interesting. Even in software development, these rarely stop at individual pieces of technology or accounts.

To show you what I mean, imagine you’re creating a photo-sharing app. Now obviously a bad actor might want to gain administrative access to this service and cause chaos that way, but what if they can’t do that? If their goal is simply to cause financial harm, they could try something less direct. Suppose they use your service legitimately, but upload illegal files en masse so that third party partners no longer want to work with you. That could shut down a business which relies on those services for weeks or months, and can’t be prevented by only doubling down on account-security measures like two-factor authentication. Even more simply, if your office isn’t locked, they could just walk through the front door and smash something with a bat.

All this is to demonstrate that your attack surface is more broad than “ways someone could get your passwords”. It could encompass physical structures, real human beings, social & political contracts, or anything else that could be manipulated to cause you harm. To identify your attack surface is to ask yourself, what am I afraid of, and what am I not afraid of yet that I probably should be?

Describing Threats to Others

This is the point where our peers can really start to provide valuable feedback, and it’s going to become useful pretty quickly to have some shorthand to describe groups of similar problems. One solution could help mitigate multiple branches of the tree, and multiple risks could be described using the same shorthand.

In software development, there are a number of industry-standard threat modeling frameworks that you can use to describe types of threats. One of the most famous is the STRIDE model, which is an acronym coined at Microsoft in the early 90’s that broadly categorizes types of security vulnerabilities that can be mitigated early in development of a system. Those categories include:

Spoofing - Pretending to be someone that you’re not.

Tampering - Changing data that your system relies on, such as a balance in a banking database.

Repudiation - Efforts to hide unauthorized activity or create plausible deniability, such as by deleting logs, disabling auditing tools, or falsifying a receipt.

Information Disclosure - Intercepting information that you’re not supposed to have. This could be a man-in-the-middle attack, collecting details on clients or projects, etc.

Denial of Service - Disrupting access to a service entirely, so that nobody can use it. This is close to our illegal-file example above, but could also include things like overwhelming a server. Even if it isn’t taken down completely, the performance impact and associated slowdown might be enough to cause the desired harm.

Elevation of Privilege - Exploits which allow a user to designate themselves as trusted. Imagine setting up a Discord server, but giving new members the ability to modify roles and server permissions.

There are lots of other risk assessment models, and if this is something that interests you, the resources available from OWASP or the Threat Modeling Manifesto would make for excellent followup reading.

Practice makes perfect, though, so lets get our hands dirty and apply these concepts with our hypothetical scenario, featuring McPersonface. These won’t all map to the STRIDE model directly, and in fact I’m not even going to try, because of how many of these concern physical space and hardware rather than transfer of data. But that’s okay. We’re solving a novel problem, after all.

Our “attack surface” will be comprised of all of the things which could be used to create the negative outcomes we’ve identified. A first pass at such a list would include:

- Our technology, including:

- Phone

- Desktop

- Router and existing wireless network

- Google Home, Chromecast, and other Google tech.

- IoT devices which can be controlled over the network

- Websites for which we have previously created an account

- Our home, including:

- Doors, specifically locks

- Windows

- Vents, if you’re paranoid

- Maintenance or other individuals with “admin access” to our physical space

- Our social network, including:

- Friends

- Co-workers

- Moving crews

- Any present or former Google employee

If you’re working on a complex system or with a larger group, you’ll want to record these in a way which is easily scannable. This will facilitate discussion and brainstorming! You’ll also want to indicate which risks are most important to you or your organization. Not all risks are created equal, after all; some are more likely than others, and some are more severe than others. So we should classify them! Otherwise we may waste an hour trying to mitigate the remote risk of “McPersonface launches an IED into our window”.

There are a lot of different ways to classify those things, depending on your industry and how qualitative you need those measurements to be. You could use something like the DREAD model (Damage, Reproducibility, Exploitability, Affected Users, Discoverability), or one of the less subjective models provided by OWASP. Personally, my background is in healthcare software, so I’m going to use a lazy version of an industry-standard risk matrix which we might employ to evaluate dangers to patients in a clinical setting. If it’s good enough for the FDA, it’s good enough for me.

I’ll provide just a couple to give you an idea, otherwise this article will end up a novella, 1 but there could be dozens of these normally!

| ID & Type | Description | Harm | Severity | Likelihood |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk 1, Physical Access | Attacker picks lock on entrance, gaining unauthorized access. | Physical violence, vandalism, surveillance, or unwanted social interaction. | Very High | Medium |

| Risk 2 Information Disclosure | Attacker monitors text messages on compromised devices. | Attacker is empowered to stalk or gaslight based on data discovered. | Low, but Creepy | High |

| Risk 3 Information Disclosure | Attacker socially engineers access to Google service outside their department. | Attacker tampers with data to create financial or social harm. | High | Medium |

| Risk 4 Shenanigans | Attacker goes back in time, trains a dinosaur in the art of Krav Maga, equips with Gatling gun and sets loose on America in the present. | Mass destruction of civilization. All human life is exterminated. Dinosaurs rule the earth and are unstoppable forces of terrible might and cruelty for all time. | Mind Shattering | Pretty Low, TBH |

I think you get the idea.

🎉 Self Care Break!✨

At this point, we’ve taken our best shot at identifying where attacks might come from. It’s really important to remind ourselves that even this is a non-exhaustive list, but that’s okay. In practice, information security is a perpetually evolving game of cat-and-mouse in which both sides continuously evolve their strategies. Our safety plan is going to require ongoing maintenance no matter what, and in a way, that frees us from having to be perfect. So even though this hypothetical scenario is high-stress and high-stakes, let’s take a second to brew some tea, read a good book, and give our security sidekick’s belly floof a proper scritching.

Did you know that cats are attracted to the scent of oelic acid, which is emitted by ants upon death? Me neither. Cool! 😺

“I smell suffering. I am summoned.”

Rested and refreshed, we’ll focus our attention on the highest priority mitigations first; our worst-case scenarios. We should also keep in mind that the purpose of our cross-country move is to increase joy, so those mitigations should wherever possible preserve our agency. No nuclear bunkers, let’s keep this reasonable.

Mitigations

Now for the fun part. It’s also the stressful part. A thing can be two things at once.

Starting with those the most urgent risks, we’ll brainstorm ways to reduce either or both its severity and likelihood, until it is below our tolerated risk threshold. That is to say, we probably can’t make them zero, but low enough that our day-to-day business can continue safely.

In our scenario, the most unique and urgent risks stem from two key facts; our attacker knows more about technology inside of our home than we do, and also that they potentially have insider access to a company that houses and profits from immense amounts of private data. So we might add a column of these mitigations to our risk matrix, including things like:

- Discarding unnecessary, networked hardware in our home, particularly anything that requires a microphone or camera to operate.

- Reviewing online user manuals for unfamiliar pieces of technology in our home, especially ones that we did not install ourselves.

- Creating new, separate accounts for services that were once shared or linked (photo sharing, banking, Netflix, etc).

- Migrating to encrypted methods of digital communication, such as Signal.

- Enabling two-factor authentication wherever possible

- Changing all of our existing passwords and using a password manager

- Transitioning from Google hosted services such as email, file storage, or GPS tools

We could continue like this for quite some time, and we’d find some potential mitigations such as “build a rocket and live on Mars” or “resolve never, ever to leave our home” would technically mitigate the risks on our list. However, these would come at the expense of lowering our quality of life (or are otherwise too expensive to be feasible). At some point, you do either need to either consider a risk as sufficiently mitigated, or come to accept that a change in plan is necessary because it simply cannot be reasonably mitigated.

Auditing

But we’re not done yet! Our mitigations are, at best, a hypothesis. There’s another super important step here, one a lot of smaller tech companies overlook.

As we talked about earlier, information security is a constantly changing landscape. Since we don’t want our attacker to adapt to a set of rigid, fire-and-forget protocols, we’ll need a system of measurement to monitor whether or not they’re having an effect, and we’ll need to commit to changing things in-flight if and when complications occur.

In software development, we would probably accomplish this by investing a few development cycles in creating a robust system of access logs and automated alerts. That is to say, a record of who accessed what and when, and a cascading set of alarms to sound when something unexpected occurs (such as a service going down, an unusual number of API requests, or when malformed data is detected in the system).

Our hypothetical situation is a little different, but we can take similar precautions in real life which fulfill the same purpose of telling us when something is wrong. If we were to install a security camera, we could configure it to send an alert to our phone if movement is detected while we are not at home. If a service that we use, like Spotify, shares access logs, we could commit to checking those once a month to make sure there aren’t any logins we don’t recognize. And we can ask friends in our network, in advance, both to not share information about us with McPersonface, and to give us the heads up if they’re asked. Steps like these allow us to continually collect information on whether our mitigations are working as expected.

We should also think about what we would do in the event that a mitigation is unsuccessful. Say we replace our locks, but our home is breached anyway. It may be helpful to document a response plan; in this case, this might involve staying at a friend’s house instead of going home. Similarly, two-factor authentication might give us a heads-up when someone attempts to access an online account, and we could resolve to either change our passwords or shut down the account entirely when this occurs. By planning these out and communicating in advance of a security event, everyone already knows how to behave and can more quickly get “on-script”.

This concludes our lesson on super basic information security. Thanks for reading!

… oh hey, couldn’t help but notice you’re still here.

Perhaps you’d be interested in a story?

Let’s Cut the Crap

At this point you’ve surely seen through the thinly veiled hypothetical bit that I’ve been doing. You’ve also probably noticed that we haven’t really given any tangible advice to survivors of abuse who live under the shadow of major tech companies. Let’s fix both of those.

The truth is, I’ve been wanting to write about my own experience with this exact scenario for…maybe a year now? And I’ve had a couple of false starts. I always end up scared to share it, in case it draws the wrong kind of attention. So writing a long-winded article on baby’s first infosec is a compromise, a factor in my own personal risk mitigation plan. After all, who the hell is going to read this far?

Well, you have. And maybe it’s because you need it. So, from here on out, I’m going to talk directly about my own experience, and arm you as best I can with something a little more practical.

The long and short of it is that this summer, after a great deal of stress, I was finally able to build a safe space, verifiably free of an ex-partner whose specter had been living in it rent-free.

In doing so, I discovered a problem with almost zero resources available on the entirety of the internet, an experience which is probably shared by many partners of employees at today’s largest tech companies and government agencies.

They say you should write the thing you want to exist but doesn’t. Well, here you are.

Red Flags

I dated my own McPersonface for maybe two years, though I’d known him for much longer. In that time, he was physically, emotionally, and sexually abusive. Our relationship was an open one, so in addition to my own mistreatment I was granted fleeting glimpses of his mistreatment of his other partners, and treated to the sort of one-sided explanations you might expect from that kind of person.

The specifics are, frankly, none of your business, and unpleasant to read besides. But a few key pieces of information may help some in the audience see themselves in this story.

🚩 He had control over what technology we would use in the house.

🚩 He had elevated or private access to many of those tools.

🚩 Sometimes, only he knew how they worked.

🚩 They often broke when he wasn’t there.

🚩 He had a habit of referencing private information he should not have known.

🚩 He often had or requested unsupervised access to our devices.

🚩 He had a history of snooping without the consent of others.

🚩 He would often brag about his ability to manipulate others.

🚩 Every one of these points was observed by others in the household.

🚩 Most importantly, he now worked for a surveillance tech megacorporation, one of the richest in the world.

I’d successfully managed to cut most of him out of my life that night when I packed my belongings into a truck and literally fled, with the help of a treasured friend. I’d cut out the rest not long after that, when he sexually assaulted me at a party, in the bedroom that used to be mine, stalking me from service to service on the internet in order to convince me it was my fault, actually. But even years later, traces of the control he used to have would pop up from time to time.

It casts a pall over your entire life. Every time your phone microphone keys, or your camera activates when you’re not using it. Every login you don’t recognize. You have to wonder, did I get it all?

They may not have been his doing. I recognize that statistically, my mitigations were overkill. But both the capability and the motivation were there, and I knew I would never, ever feel safe again unless I decontaminated my new home and retook control of my life. I think you can’t understand it, unless you’re a survivor.

Here’s how I did it, step by step. 2

Establishing a Safe Zone

I began with a couple of assumptions.

- Any hardware which he had physical access to must be considered compromised.

- This included traffic over my home network, which he had helped set up.

- Any digital account which had passwords saved on a compromised device or service is also compromised, itself.

- Messages which were sent over compromised devices or networks were as good as in his inbox.

- Any service which was owned by Google was essentially a surveillance tool and therefore compromised by design

This is a very wide net, and would capture things that were probably fine. But I decided we were going completely, 100% scorched earth, out of abundance of caution. I made a deal with myself; if I succeeded within these constraints, I would allow myself to feel safe again and live normally.

Since this included my phone and current email addresses, I had to consider the possibility that changing any passwords or systems would generate an alert he could read.

I would need to proceed in a specific order. Fortunately, I work in tech, so I had colleagues that I could tap for advice, if I could reach them.

I left my phone at home, and physically knocked on a friend’s door. They also met me without any devices, and we took a walk out of earshot of technology.

They agreed to lend me their devices and network if I needed them, and for that support I am eternally grateful. I ordered a small, cheap faraday shield; these are containers that blocks electronic signals, first invented by Michael Faraday in the early 1800’s. You can actually build one DIY style if you’re desperate, with a couple of components. I recommend buying things in cash if you can, in case your banking records are being monitored or you share a joint account. Worst case scenario, withdraw $20 or so, use that to buy a pre-paid gift card at Target or something, and use that gift card to make digital purchases, mailed somewhere safe.

To be clear, the faraday shield was probably overkill. Airplane mode isn’t sufficient for our purposes, since many apps will queue up data to phone home when connection is restored. When you turn off your phone, though, that’s usually enough. It stops reporting to cell towers and sending data in general.

However, it is possible for spyware to circumvent this by forcibly powering on your phone again for a few seconds at an interval. You can take it a step further than that by removing the battery, but the NSA claims it can triangulate phones which have the battery removed. Unless your attacker works for the government you probably do not need to go this crazy with it, but please remember that’s only as of writing (2021). Technology changes rapidly and this may not always be true. I’m not a wizard. 3

With the battery removed from my unpowered phone, and placed in a faraday shield, I could be reasonably sure it wasn’t tattling on me.

I printed some directions to a new cell phone carrier. At minimum, I needed a new phone number, and a new SIM card. Some carriers will do both of those for you for free, others might ding you $20 or so. 🤷 This is to help mitigate the potential for SIM swapping attacks; where you essentially convince a carrier that someone else’s number is yours, allowing you to intercept messages and access accounts which use that for authentication.

The folks at my new carrier were gracious (if horrified) by my explanation of why the faraday shield was necessary, and they agreed not to speak when it was out of the case.

Since McPersonface had often had unsupervised access to my phone, and I was noticing my mic and camera key when the phone was not in use, I took it a step further and purchased an entirely new phone.4 I think for most people, this will be overkill, and infosec friends agreed; the most commonly used monitoring methods will require a phone to be jailbroken in order to function. However, this is the one place I decided to overrule advice from my security advisors. There is a thriving industry of “girlfriend tracking” apps, often marketed as “family protection tools” to skirt app store policies, which do not require it, and it can be difficult to tell if they were installed without your consent. Even my most tuned-in infosec fam considered this new information; it’s not reported on very often.

Plus, I think it’s unwise to take “it’s not possible” as gospel. A few years ago techies would claim Macs couldn’t get viruses and that iOS was a bastion. Now Pegasus exists. Engineers have blind spots, new exploits are discovered all the time, and the only thing that’s guaranteed is that no software is perfectly air-tight. Technology marches on, for better or worse.

Now that I had a verifiably clean device, and an LTE network which couldn’t be monitored by the attacker, I had established a safe zone.

As long as I did not connect my phone to my existing network, I could begin to create new accounts for services I’d need within the quarantine zone, and maintain confidence that they could not be accessed or intercepted by my attacker. Then it’d just be process of hosing down “compromised” accounts, beefing up their security, and adding them to the pile. Note that doing this with a phone is incredibly tedious, so if you’re willing to lean on a friend’s hardware you can do this on another desktop. Many services will require a phone number on sign-up, though, and we’re going to want to take back the compromised accounts that we can, so I highly advise having this sorted out anyway.

A Quick Intermission

This is as good a time as any to address the most likely counter-argument that Google, or indeed my attacker, would make if this were a dialogue, to convince me that I’m paranoid or stupid. Specifically, that any tech company worth their salt will implement an access control policy that will prevent employees who do not need it from viewing customer data. This argument is garbage and I’m going to go ahead and put it to bed now.

First, Google specifically does not have a good track record with this. Reports as recently as 2020 show that Google employees can and do access data, including customer data, that they should not have access to. This is not unique to Google, though. Practically every company has this issue. In fact, government entities such as the NSA has a history of employees using tools ostensibly meant for counter-terrorism (dog whistle dog whistle) to spy on or abuse their spouses instead. Company or agency, every single one of them will give you some boiler-plate about blah blah privacy is our top priority, but it still happens and ultimately nobody is ever held accountable for it.

Second, tech companies are lazy. I know this because I work for them and it is the bane of my existence. The saying is move fast and break things, not move fast but oh wait actually take a few extra sprints on that Joe it pertains to customer privacy. I’ve lost count of the number of times otherwise reputable companies, even ones I’ve worked at, have cut corners in order to ship quickly, or turned a blind eye to protocol when it becomes onerous, with the promise to come back to it later. I know first-hand how hard it is to push the “do the right thing” boulder, working at companies with only a tiny fraction of the bureaucracy and money in play as Google.

Third, your access control policy is only as good as the team enforcing it. Companies are staffed by people, and people are shitty. They make mistakes, they take bribes, they’re perverts, they can be manipulated. Even if the software managing access control was perfect, it takes one idiot to undo it. If I already don’t trust you, why would I delegate trust to all the people you trust?

Finally, no company is ever going to be transparent about this unless they are forced to be. They have to be caught. It’s just not in their best interests to disclose this if they don’t have to. So if they find McPersonface toying with my Google Home, they might do a lot of things, from coaching to termination, but they’re sure as hell not going to tell me. Better to just cut them out.

Decontamination

Okay, next step, email. So, so many accounts that we use are tied to our email address or phone. Securing this was crucial. I had previously been using Gmail, and for reasons we just discussed I was eager to migrate. I opted for creating an entirely new email address, and would generally recommend this if you find yourself in my situation.

If you have the means, I recommend selecting a paid service like Fastmail or Protonmail. It’s practically a cliche at this point, but if you aren’t paying for the product, you’re the product. And if you’re reading this in the future, do a little homework on your clean network to see which services are reputable these days. With my luck I’ll recommend something and they’ll have a scandal in like a year.

I broke the golden rule of armchair infosec at this point, and wrote that new password down on a piece of paper. If you’ve played Deus Ex, you’re probably really confused why I would choose to do something like that, but given my device was compromised and I had ticked the “remember me” box for my password manager (never do that), I had to assume that one was shot. The one piece of technology my attacker could not gain unauthorized access to in that moment was a sticky note.

The moment you’ve got that new email address, the very next thing you’re going to do with it is set up two-factor authentication or MFA. This is essentially a temporary, second password, which is unique to a moment in time and increases confidence that you’re the real owner. Since we just went through all that trouble with SIM swapping, I selected an authentication method that was not SMS based whenever possible. Services like Twilio’s Authy or even the accursed Duo Mobile are easy to set up. Obviously, don’t pick one hosted by the megacorporation you’re trying to avoid.

I’m not going to repeat this every time I do it, but assume that every new account from here on out gets an MFA setup like this.

Again working off of the assumption that my password manager was compromised, I set up a new one. There are lots of these to choose from, too. The most popular ones are Lastpass, 1Password, and Bitwarden. Some of these can even be self-hosted if you like, though that’s probably too much work to do at this early stage. I put the email credentials in here at this point so I didn’t need to carry it on paper.

My next step was to skip merrily around the house and yank all of my hardware out their outlets.

Honestly this was kinda fun, like spring cleaning. I wrote “BOX OF SHAME” in thick sharpie on a cardboard box, and filled it with every Google device, everything he’d ever purchased, that I didn’t understand how to use, or that had been added to my home without my consent.

In the end, it contained several Google Homes, a Chromecast, a Google Router, a modem (for a network he set up!), game consoles, a computer he had built for me, and a few other items which contained (or literally were) microphones or cameras. I set two of them aside for now though; the router, and the desktop. I needed them for a few more hours to complete the purge, but I did make an appointment with my ISP to terminate my old account so I could set up a brand new network as soon as possible. 5

Now the tedious bit. I sat down with my two devices; a “compromised” one from which I would access all my old stuff, and my nice clean one. And let me tell you, this step takes a LONG time.

Starting with my old email addresses, I’d run through the following steps.

- Log into the account.

- Run through any available “security checkup” (Google at least has them) and remove every registered device, third party app, and recovery email.

- Force logout currently logged in devices on the account.

- Un-link any current MFA tools, especially when it referenced my old phone number.

- Change the password to a temporary one I had generated on the “clean” device.

- Change all recovery questions to gibberish ones that don’t even correspond to my real life, which I stored in the “clean” password manager. (This makes it harder to socially engineer access or brute force recovery options, since we’d lived together)

- Set up MFA on the account, using my new device.

- Change the password again in case the attacker happened to be monitoring at that exact moment, and store in the clean password manager.

I repeated this for literally every account I owned and wanted to keep, as closely together as I could to minimize heads-up that McPersonface might be given if they were monitoring any of those accounts. It’s vital in this process not to allow final passwords or contact information to be entered on the compromised device or network.

Even this, technically, leaves about a 30 second window with which the attacker could still be in each account taking note of some changes. But remember what we said before about over-mitigating? No nuclear bunkers here, there is a limit to what we can reasonably do. And anyway, if your attacker is able to do this, your adversary is probably a government entity and you’re beyond anyone’s help in that respect.

There were some accounts that just did not have a robust enough set of security settings for me to safely move, so I nuked them from orbit. I had already done this years ago with all of my social media accounts when he was stalking me across the internet, so it didn’t sting too much.

Some accounts didn’t have deletion options either, if you can believe it, so I wiped as much of my data from those as I could, and settled for changing the password and leaving it to rot.

One of my lovely dispensers of infosec wisdom recommended you never fully delete an email account, but instead set up forwarding to your new address.

I did mess this one up and ended up losing access to a couple of accounts I wish I hadn’t, so, um, just highlighting to listen to my support network on this one. Oops!

When I was done with this process, I reformatted the old desktop, and added it along with the modem and router to the shame pile for DEMOLITION. You should always use care when disposing of things with built-in storage, like game consoles, your PC, or other things that may have contained credit card numbers in the past, as even “deleted” data is surprisingly easy to recover. Most delete functions are misnomers. They actually just remove the reference which points to the data; it remains intact until that sector of storage is needed again and is overwritten. This is more of a best practice than a risk we need to mitigate, our attacker probably isn’t going to fly across the country to roll around in our trash.

I set up my new network myself, so I knew how it worked, using a one of Ubiquiti’s more security-oriented routers. To help camouflage my new setup a bit, I resisted the urge to set up a witty wifi network name that sounded Val-ish, and just used something machine-generated that would blend in with the surrounding apartments.

One thing that I haven’t really mentioned so far was the need to switch browsers. I’d been using Google Chrome for a while, and ended up moving to a combination of Mozilla Firefox and Tor. A lot of alternatives to Chrome are still based on Chromium, so keep an eye out for that and avoid them just to be on the safe side.

I made sure not to install any unnecessary apps on my new phone, to minimize pipelines my data could be in. Obviously I’ve replaced everything that depended on a Google service with something else, too, resecured my Apple ID, and ran through extensive privacy and security checkups.

It took a while, but eventually I built my own PC from scratch to replace the one I had tossed. Some things, I didn’t replace at all, and when I absolutely had to, I took care to select services and technology at competing mega-corporations which I can be reasonably sure, for anti-trust reasons, can never be purchased by Google.

It does mean I have an ongoing commitment to make sure he hasn’t hopped to another company, but even if he does, I’ve secured my digital life enough that it won’t be a huge deal. A few targeted data deletion requests, at the most, rather than a full-on purge. I do think eventually this will be a wider, more difficult to solve problem as our capitalist hellscape continues to disolve, but for now it’s a level of risk I can live with.

MeatSpace

Now, since I’ll be re-homing soon, possibly in a closer proximity to McPersonface, I’ve also got a bit of physical risks to mitigate. I’ve long since changed my locks, so that’s not something I needed to worry about going into it.

I did a bit of research on security camera options; which ones could be closed-circuit vs exposing my feed to the internet, and which ones could reliably be shielded from acquisition by Google. I’ve also done a little planning on how they could be positioned, so that I always have control over what is in the feed, and so that I can physically kill the power to them when I don’t want them running. Remember, for every piece of IoT technology you add, you’re increasing your attack surface area and the type of data which can be collected on you without your consent. Make sure it’s worth it!

I bought a baseball bat, and learned to box. I’m considering investing in a nice saber, and learned how to operate a stungun. Holy shit, they’re loud.

I can verify independently with my network that where I choose to live isn’t live near him or his office, to maximize space between us. I’ve got an agreement with every mutual friend and acquaintance that information about me is not to be shared, and have a plan for what to do in the event my home or locks are breached, or I think I’m being followed. I plan to have a frank conversation with office management if I end up relocating into an apartment, to reduce McPersonface’s ability to sweet talk maintenance or utility crews. I have a backup location selected in case I want to steer clear of the whole state.

Obviously my job hunt excluded all positions with Google or Alphabet subsidiaries, which kind of stung because they pay well but to be honest I don’t want to work on surveillance tech anyway.

Wrapping Up

The last step was to write an appropriately vague, plausibly deniable, but very detailed blog post about my experience, which makes it absolutely unambiguous that he is on notice; that I am not fucking around, have grown into a formidable, independent, and badass bitch, and am not to be trifled with or contacted ever, under any circumstances. Really put my dick on the table.

Now, you could make an argument that it would be a better security practice not to document any of these things anywhere, to jealously hide this knowledge, but remember that self-care break? Our security practices should restrict our self-expression and ability to pursue personal and business goals as little as possible. Besides, I’ve never really been a fan of relying on security-through-obscurity.

So, was all of this shit worth it?

Absolutely.

Today I am confident that every piece of technology in my house is working for me. It’s going to require ongoing monitoring and could realistically shift at any time, but for now I feel powerful, and in control. I learned a lot, and it turns out the whole “Val stupid and can’t computer” thing was a story my abuser created about me with no basis in reality. With a bit of research and the help of some friends who cared, I was able to learn what I needed to know just fine and even established an extra baseline of infosec knowledge to help me in my career. I still have a lot to learn, but today I partner directly with my security teams to work on problems kind of like these!

This state of inner peace is attainable, so more than anything I’d want survivors to know that you can do it, and it’s not insurmountable.

But the fact of the matter is that this shouldn’t be necessary, and at least for me, it was fucking expensive. This is a seriously under-reported horror scenario, and to the best of my knowledge, there just aren’t resources like this out there for survivors. I had more at my disposal than most will. If it was this bad for me, just imagine.

As companies like Google, Amazon, and Facebook grow in scale, launch new products, and collect more and more data on citizens, these situations are going to become more common. Humans can be cruel to each other, and companies are just collections of humans. At a certain size, you’re bound to have some absolutely lunatics on the prowl.

I don’t have the answers on how to fix this, but I know it’s urgent. I also think it’s maybe not my responsibility to fix to begin with. It’s FAANG’s.

Just some food for thought.

Something I will always, always remember and appreciate is how gracious my support network was during this process.

For a lot of it, they were on a call with me as I described what I was doing, and answered questions when I was unsure how to proceed with some of the more bespoke accounts and processes. To be totally honest, I still messed up a couple of times, but they were kind about that, too. Most software companies also fuck up once or twice. It increases your risk but isn’t the end of the world. You include it in the post-mortem, learn from it, and move on.

They were honest when they thought something was more trouble than its worth, accepted counterarguments when I could support them with research, and most importantly believed me when I told them I was afraid. They accepted the conceit that my space was compromised, and helped me create a space I could feel safe in. Because if I was wrong? It was still a cool thought experiment, and a learning opportunity for all of us.

Thanks fam, I appreciate you.

If you’re wondering whether what you’re experiencing is domestic abuse, there are always people who can help safely and anonymously.

The most popular one is the National Domestic Violence Hotline, based in Texas and recommended by the US Department of Justice for this purpose. Most states have their own, too!

And if you’re worried about your browsing history being monitored, then you can call the hotline directly at 1.800.799.7233 instead.

Stay safe, fam!

Citations

Kohnfelder, Lauren & Garg, Praerit via Shostack, Adam. “The threats to our products” Microsoft, 01 April 1999, https://adam.shostack.org/microsoft/The-Threats-To-Our-Products.docx.

Conklin, Larry & Drake, Victoria. “Threat Modeling Process”, OWASP, Accessed 1 January 2022, https://owasp.org/www-community/Threat_Modeling_Process.

“Threat Modeling Manifesto”, Multiple Authors, Just Like, Geez, Man, A Whole Bunch, Accessed 1 January 2022, https://www.threatmodelingmanifesto.org.

Bowles, Nellie, “Thermostats, Locks and Lights: Digital Tools of Domestic Abuse”, The New York Times, 23 June 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/23/technology/smart-home-devices-domestic-abuse.html

Gallagher, Ryan, “NSA Can Reportedly Track Phones Even When They’re Turned Off”, Slate, 22 July 2013, https://www.threatmodelingmanifesto.org.

Barret, Brian, “How to Protect Yourself Against a SIM Swap Attack”, Wired, 19 August 2018, https://www.wired.com/story/sim-swap-attack-defend-phone/

“Control access to hardware features on iPhone”, Apple, Accessed 1 January 2022, https://support.apple.com/guide/iphone/control-access-to-hardware-features-iph168c4bbd5/ios

Nicki Dell, Karen Levy, Damon McCoy, & Thomas Ristenpart, “How domestic abusers use smartphones to spy on their partners” Vox, 21 May 2018, https://www.vox.com/the-big-idea/2018/5/21/17374434/intimate-partner-violence-spyware-domestic-abusers-apple-google

Lyons, Kim, “Pegasus spyware used to target phones of journalists and activists, investigation finds”, The Verge, 18 July 2021, https://www.theverge.com/2021/7/18/22582532/pegasus-nso-spyware-target-phones-journalists-activists-investigation

Cox, Joseph, “Leaked Document Says Google Fired Dozens of Employees for Data Misuse”, Vice, 4 August 2021, https://www.vice.com/en/article/g5gk73/google-fired-dozens-for-data-misuse

Jackson, Sarah, “A Facebook engineer abused access to user data to track down a woman who had left their hotel room after they fought on vacation, new book says”, Business Insider, 13 July 2021, https://www.businessinsider.com/facebook-fired-dozens-abusing-access-user-data-an-ugly-truth-2021-7

Selyukh, Alina, “NSA staff used spy tools on spouses, ex-lovers: watchdog”, Reuters, 27 September 2013, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-surveillance-watchdog-idUSBRE98Q14G20130927

Keck, Catie, “Amazon’s Ring Security Cameras May Have Let Employees Spy on Customers: Report”, Gizmodo, 10 January 2019, https://gizmodo.com/amazons-ring-security-cameras-may-have-let-employees-sp-1831658669

Cox, Joseph, “Amazon Fired Employee for Leaking Customer Emails”, Vice, 26 October 202, https://www.vice.com/en/article/dy8zwz/amazon-fired-employee-leaking-customer-emails”

Robertson, Adi, “Used Xboxes can be hacked for credit card information, researcher says”, The Verge, Kotaku, 30 March 2012, https://www.theverge.com/2012/3/30/2913726/used-xbox-credit-card-information-hack-research

Whitney, Lance, “How to recover deleted files”, Engadget, 31 July 2018, https://www.engadget.com/2018-07-31-how-to-recover-deleted-files.html

Kelly, Heather, “Apple iOS privacy settings to change now”, The Washington Post, 14 December 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2021/11/26/ios-privacy-settings/

-

Editor’s note: it is in fact a novelette. ↩

-

If you’re reading this from the future, you can replace “Google” with whatever all-seeing, omnipotent corporate eye you’re trying to avoid. If it’s a government entity, I can only kind of help you. ↩

-

I’m a witch. Totally different. ↩

-

Just acknowledging that my privilege is showing here, and that this is outside the means of most folks on short notice. As an alternative, I would recommend pre-paid, non-smart phones. They’re much, much cheaper, starting around 40$, and usually have pay as you go plans. You can find them in most Walmarts, Targets, Best Buys, etc. ↩

-

This did confuse them a little but it helps reduce the odds of them socially engineering access back into your account if you’ve previously lived together. Plus Spectrum had been deadnaming me for a while so I was just kind of done with them. 🖕 ↩